102

102

oil on Masonite 19⅞ h × 30 w in (50 × 76 cm)

estimate: $6,000–8,000

result: $8,190

follow artist

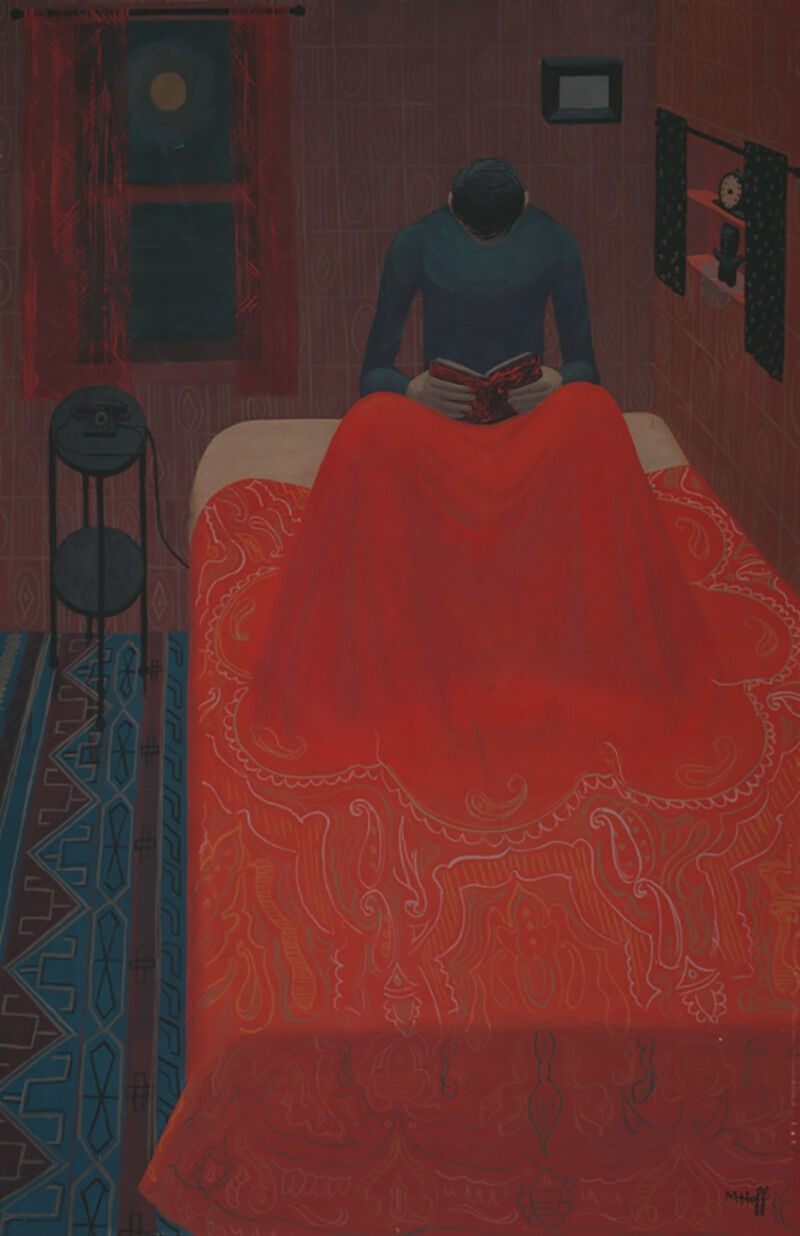

Signed to lower right ‘M. Hoff’.

provenance: Private Collection

This work will ship from Chicago, Illinois.

American artist Margo Hoff spent the first part of her career in Chicago, from 1933, when she first enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, until 1960, when she moved permanently to New York City. While Hoff trained during the prime years of Chicago Modernism—with many of her contemporaries engaged in commissions for the WPA (Works Progress Administration) Federal Art Project—she herself was more influenced by the Mexican muralists of the 1930s, like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros, along with Henri Matisse. In the 1940s, Hoff repeatedly traveled, with her artist husband, George Buehr, to Mexico to study firsthand the works of the prior decade.

Modeling the Mexican artists and Matisse, Hoff subsequently developed an uncanny ability to mix striking palettes in service of intensely naturalistic yet quite stylized renderings of interior scenes, glimpses through windows, and views of empty buildings or rooftops. Her interior scenes could require staging at times, for example, in what many deem her masterwork, Murder Mystery, 1945. The Art Institute of Chicago acquired this impressively composed, oil and casein on canvas board the year after its completion, helping to launch Hoff’s artistic career in earnest. To prepare herself for Murder Mystery, Hoff had carefully arranged the room and asked her husband to sit as the reader in bed.

Around 1950, Hoff’s figuration began to take on a temporarily more Surrealist or Magical Realist appearance. Although these stylistic designations were not labels Hoff would have identified with per se, she was part of the Art Institute's 1949 Fifty-Third Annual Exhibition by Artists of Chicago and Vicinity, which included more explicitly Surrealist work by Gertrude Abercrombie. Many of the figures in Hoff’s scenes during the 1940s appear to have a haunted, or eerily still, quality at least, especially the children. Magic Bubbles, c. 1947, which is also held by the Art Institute, shows a boy and girl at play blowing bubbles, albeit both in suspended animation. The boy has his back to the viewer, but the girl—perhaps based on Hoff’s daughter, Mia Buehr, who was born in 1942—looms almost doll-like, her hands raised to catch bubbles, but suggestive of someone under arrest. Hoff’s mesmerizing, oil on Masonite painting, Dream of Flying, 1950, was reportedly inspired by a dream that her daughter had. Yet the levitating, female figure appears poised between two worlds, floating between consciousness and oblivion. Is this a portrait of peaceful, childlike slumber or a more ambivalent state of being, presaging an eventual loss of innocence?

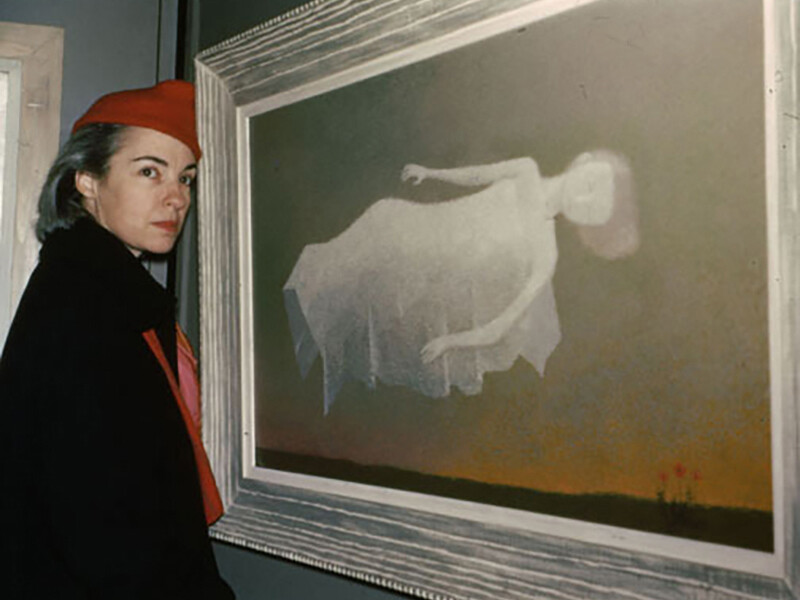

In 1955, Hoff won the art contest at the Magnificent Mile Art Festival in Chicago with a painting entitled Butterflies. The reward was a one-person show at the esteemed Wildenstein Galleries in Paris. Altogether, thirty-one works by Hoff were exhibited, but, given French customs rules, none of the paintings could be sold in Paris. Therefore, the complete exhibit was recreated in Chicago at Fairweather-Hardin Gallery. As seen in the period photograph below, Frederick Sweet, Curator of American Painting & Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago, selected among several examples of Hoff's artwork to compose the show that traveled to Paris, in consultation with Vladimir Vissen and J.W. Alsdorf (not shown). Hoff’s Dream of Flying is pictured in the upper-right corner of this photo, with not only Murder Mystery below, but also another work, Women, Children, and Bridge, which Toomey & Co. sold for $6,250, including premium, during the Art & Design auction on June 24, 2018.

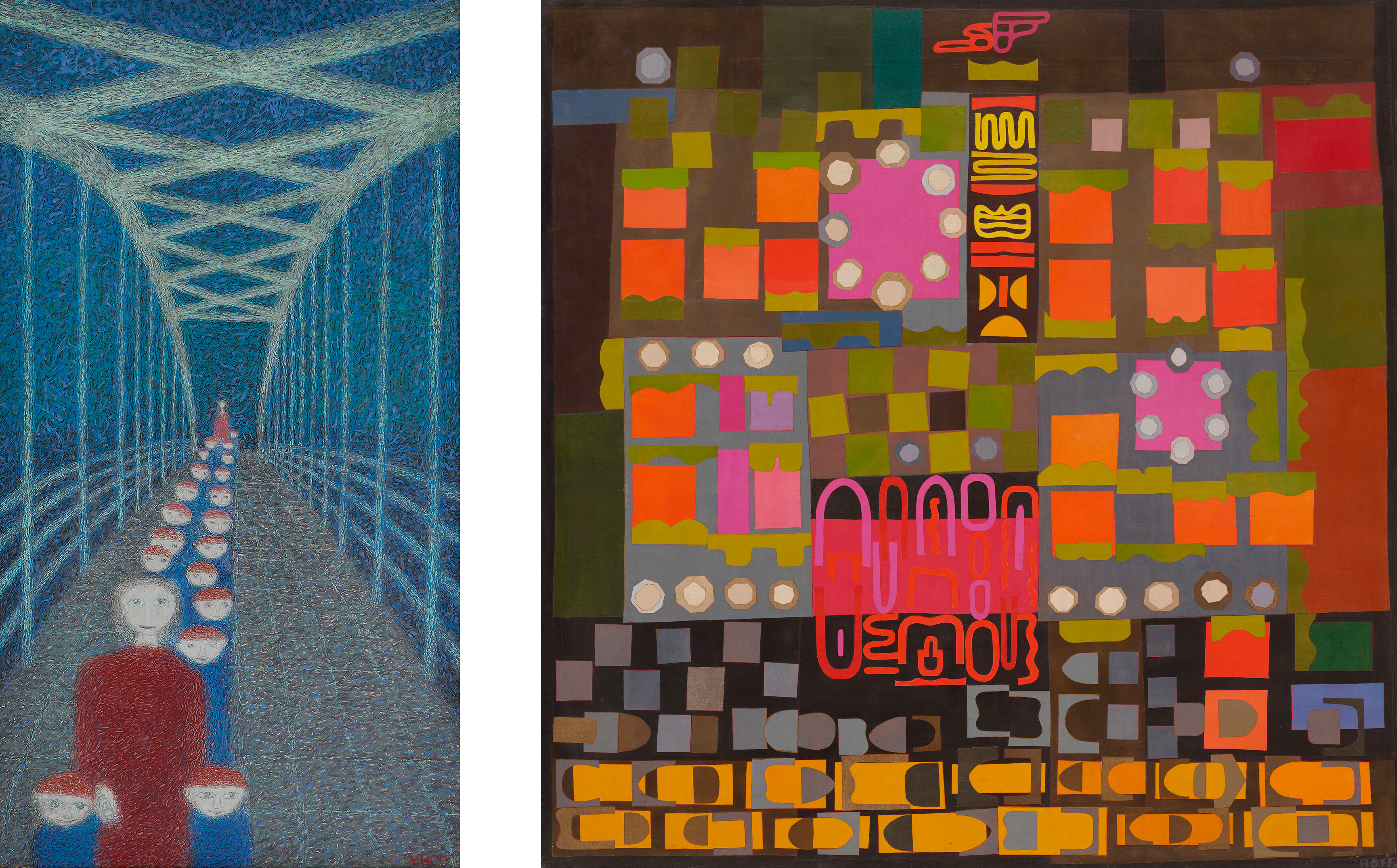

Despite Women, Children, and Bridge being undated, Hoff certainly painted the work no later than 1954, because it was featured that year in the exhibition, Steel, Iron, and Men, at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama. Whereas Dream of Flying is a vivid encapsulation of ethereality, Women, Children, and Bridge looks evanescent by comparison, with the figures and bridge itself presented in mid-dissolve, obliquely referencing Pointillism. After Hoff’s 1960 move to New York City, her style flowed almost immediately into an abstract mode, with some works that nonetheless retained a similar gauzy transcendence. However, increasingly she shifted to collage-based investigations of form and color. In the 1974 mixed media on canvas, 2 A.M.—which realized $25,000 during Wright's Art + Design auction on July 19, 2018—Hoff expresses a pronounced Geometric Abstraction, but the work’s title and grid-like elements seem to suggest a metropolis at night, perhaps the city that never sleeps, New York. Ever in conversation with the myriad artistic currents of her time, Hoff’s itinerant life and multifaceted work were testaments to the importance of embracing change.

Broadly considered, Chicago Modernism includes works in a range of styles covering all manner of themes from the 1890s through the mid-20th century. From portraiture to landscapes, from still lifes to abstractions, and more, artists who were active in Chicago prior to the turn of the 20th century up through World War II helped to define the emerging city to itself and the world outside. This period featured notable artists producing finely executed and innovative examples of Impressionism, Realism, Abstraction, Regionalism, Surrealism, and Magical Realism. While connected to the major artistic currents in cultural centers like New York City and Paris, Chicago Modernism was able to develop in a relatively organic and original fashion given the Midwest’s geographic isolation and its tendency to be sometimes overlooked.

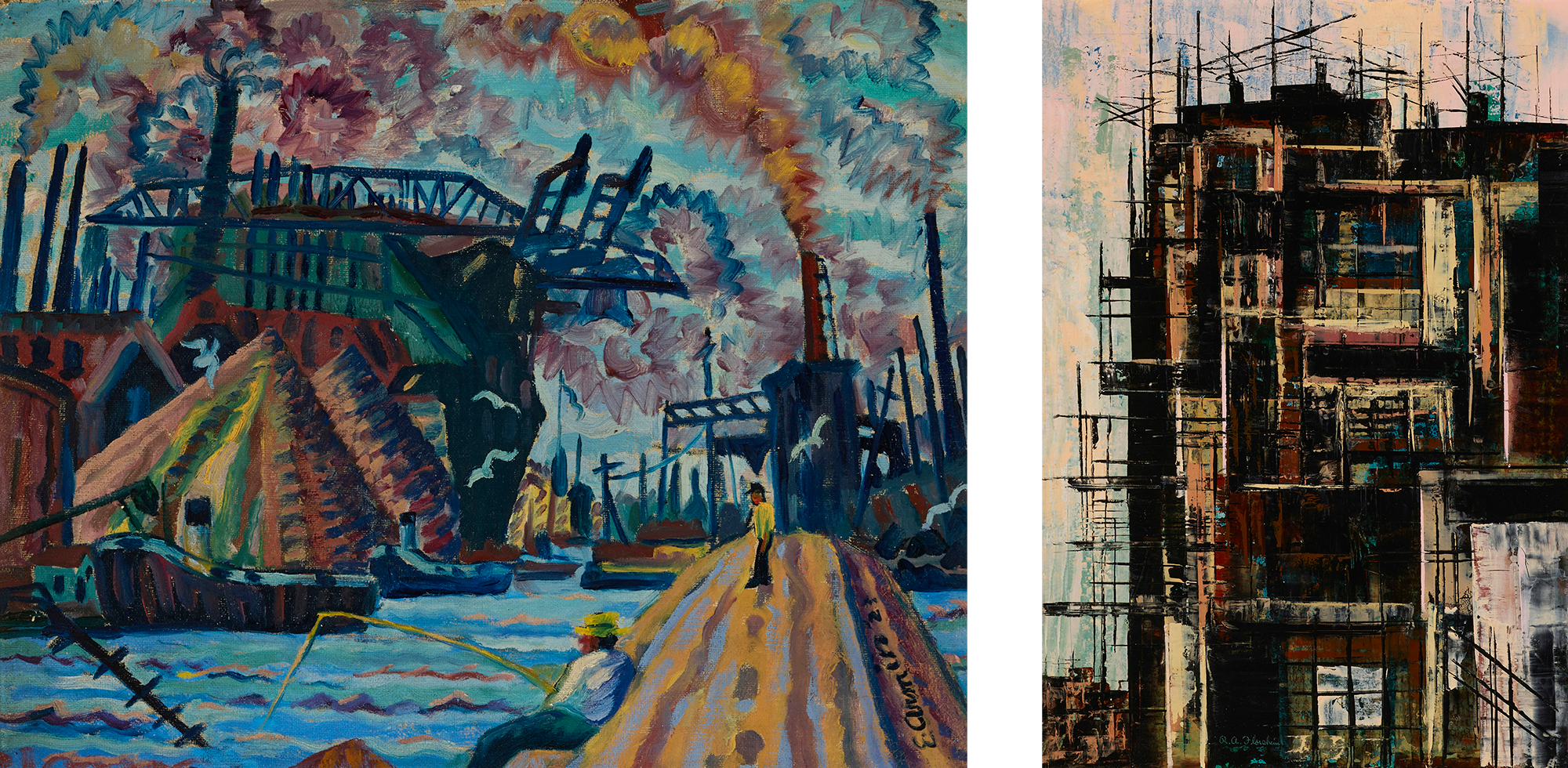

Following the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which certainly put the city on the map, in a literal and figurative sense, Impressionism, and its variants, began to take hold in Chicago, as it had already on the East Coast. When the modern era dawned, much of the Impressionist artwork done in Chicago contrasted rural and urban life or manifested as formal portraiture. Some of the key figures of this time were Oliver Dennett Grover, Adam Emory Albright, Frederick Fursman, Pauline Palmer, Frank C. Peyraud, Walter Krawiec, Carl Krafft, Karl Albert Buehr, and Alfred Juergens. The early decades of the 20th century also saw increased immigration to the United States, in particular, by Central and Eastern Europeans. In Chicago, some of these recent arrivals, and first-generation residents, sought to preserve their heritage while capturing the urban development around them. Among these were prominent Jewish-American artists like Emil Armin and Todros Geller, who exhibited with Grant Wood at the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as William Schwartz, Herman Menzel, Charles Turzak, and George Josimovich.

In the 1920s and 1930s, as the built environment of Chicago expanded, artists sought to represent this growth in their work. Many of these individuals were also employed by the New Deal-sponsored WPA (Works Progress Administration) Federal Art Project, which aimed to enhance the cultural fabric of America as the Great Depression threatened to fray the social contract. While there was some overlap aesthetically with work created by noted Regionalists like Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, the Chicago WPA artists operated in a variety of modes that ranged from Modernism to Art Deco to Abstraction. Around this time, the exceedingly versatile artist/designer Edgar Miller also began to make his mark on Chicago by blending elements of Arts & Crafts with Modernism in virtually every medium available.

Along with many of the European immigrants in Chicago, additional artists who were employed by the WPA to produce murals, paintings, prints, sculpture, and more included Jean Crawford Adams, Max Kahn, Eve Garrison, Roff Beman, Frances Foy, Harold Haydon, Rowena Fry, John Winters, Burton Freund, Hildreth Meiere, and countless others. The diversifying city was also represented in the WPA by artists of color like Eldzier Cortor, Archibald J. Motley, Jr., Jacob Lawrence, and Julio de Diego. Moreover, formally distinct Abstraction existed within Chicago Modernism by WPA artist Rudolph Weisenborn, as well as his student at the Art Institute of Chicago, Dorothy Stafford, along with the groundbreaking Manierre Dawson, Constructivist artist Paul Kelpe, Richard A. Florsheim, and Daniel Massen, who taught at the School of Design and the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Fantasy art afforded these [Chicago] artists a way of departing from tradition without abandoning many of its values: grounded in figuration and narrative, such art gave expression to highly personal visions in accordance with the aims of Modernism.” — Susan S. Weininger, Chicago Modern, 1893-1945: Pursuit of the New, Terra Museum of American Art, pg. 67

Modernism in Chicago further encompassed both Surrealism and Magical Realism. Given the city’s physical and cultural isolation, these fantasy-based art forms were able to flourish in unconventional, idiosyncratic ways. Gertrude Abercrombie, known as the “Queen of Bohemian Art,” was also a WPA artist, but, rather than presenting Chicago cityscapes or urban scenes, Abercrombie established herself on symbolic terrain. A master of self-portraits, Abercrombie inserted female figures into her beguiling works, but she was also fond of painting herself via owls, cats, horses, and other animals, or through elegantly simple still lifes with charged, everyday elements.

Among Abercrombie’s contemporaries were various highly skilled female artists, such as Julia Thecla, Helen Mann, and Margo Hoff, who each elaborated uniquely imaginative approaches to otherworldly effect. Macena Barton and Fritzi Brod were likewise accomplished fantasists whose work combined aspects of Expressionism and Folk Art. Milwaukee artist Karl Priebe trained at the Art Institute of Chicago and became known for his particular brand of Surrealism, with favorite subjects being portraits of Black figures he encountered teaching at a settlement house in Chicago as well as birds and exotic animals. Priebe was a longtime friend of Abercrombie's and they both were close with Wisconsin artist John Wilde—another proponent of Surrealism. Chicago native Aaron Bohrod faithfully chronicled local landscapes early in his career, before becoming adept at trompe-l’œil still lifes while an artist in residence at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. By contrast, Ivan Albright—son of Impressionist painter Adam Emory Albright—applied painstaking, classical techniques to render Modernism with a macabre vision and moody palette; his dark, high-relief portraits and still lifes provide a somber, yet undeniably compelling, counter to the soft brushstrokes and light-filled canvases of the Impressionists who ushered in Chicago Modernism over a half century before.

Not only did the many incarnations of Chicago Modernism serve to produce a robust aesthetic culture by the mid-20th century, but several of the aforementioned artists proved to be key influences for later generations. Gertrude Abercrombie, Eldzier Cortor, Todros Geller, and others have benefited from posthumous critical reevaluations, in which they have become more highly regarded now than they were during their lifetimes. Thematic and stylistic traces of Modernism may also be observed in the work of some artists associated with subsequent movements, such as the Monster Roster, Hairy Who?, and Chicago Imagists, proving that art history is indeed a continuum.

Margo Hoff 1910–2008

Artist Margo Hoff was born in 1910 in Carthage, Missouri, but she grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Her father was a carpenter and she was the second oldest of eight siblings. In an unexpected twist of fate, Hoff contracted typhoid fever upon turning thirteen in 1923, which confined her to bed for the summer. During this period of convalescence, Hoff discovered her passion for art, spending considerable time drawing and creating paper cutouts. After graduating from Tulsa Central High School, Hoff went on to attend Tulsa University, the National Academy of Art in Chicago, the Art Institute of Chicago, the University of Chicago, and Hull House.

Hoff's figurative approach to art was profoundly influenced by her travels to Mexico in the 1940s, where she encountered the work of Mexican painters from the 1930s, including Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. This vibrant artistic milieu left an indelible mark on Hoff, shaping her aesthetic sensibilities and thematic explorations. Throughout Hoff's life, she remained committed to her craft, experimenting with a wide range of artistic media, including woodcut, lithography, casein, oil, watercolor, crayon, gouache, collage, textiles, and stained glass.

In the 1950s, Hoff exhibited her paintings and prints across the United States and eventually had a solo show at the Wildenstein Galleries in Paris in 1955. Hoff made a pivotal choice in 1960 to relocate permanently to New York City, where her work found frequent representation in prominent galleries like Hadler-Rodriguez, Saidenberg, Babcock, Betty Parsons, and Banter. Hoff's artistic evolution was marked by a shift in style and technique following her move to New York. While most of Hoff's Chicago paintings are decidedly Modernist figurative compositions—which resemble Surrealism or Magical Realism, while actually working through a wholly original lexicon shaped by the Mexican muralists as well as Matisse—her New York period consisted largely of geometric abstraction and collage work, first on paper and then on canvas. This phase of her career was characterized by brighter colors and a departure from her earlier earth-toned palette.

Despite traveling extensively, often to teach, and gaining acclaim as a New York-based artist, Hoff remained deeply connected to her roots, with Chicago serving as a formative backdrop even in later years. Thus, she has a significant legacy as an important, if underappreciated, Chicago Modernist artist. Although Hoff died in her Manhattan studio loft at the age of ninety-eight in 2008, her ashes were ultimately interred at Graceland Cemetery on the North Side of Chicago. Throughout her lifetime, Hoff was recognized with numerous awards and honors, including the prestigious Logan Art Institute Prize. Currently, paintings by Hoff are held in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago—which has what some consider Hoff's masterwork, Murder Mystery, 1945—along with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, and elsewhere.

4: 03: 33

Design

11:00 am ct