153

153

oil on canvas 11 h × 13⅛ w in (28 × 33 cm)

estimate: $1,500–2,000

follow artist

provenance: Barton Faist, Chicago | Private Collection, Chicago

This work will ship from Chicago, Illinois.

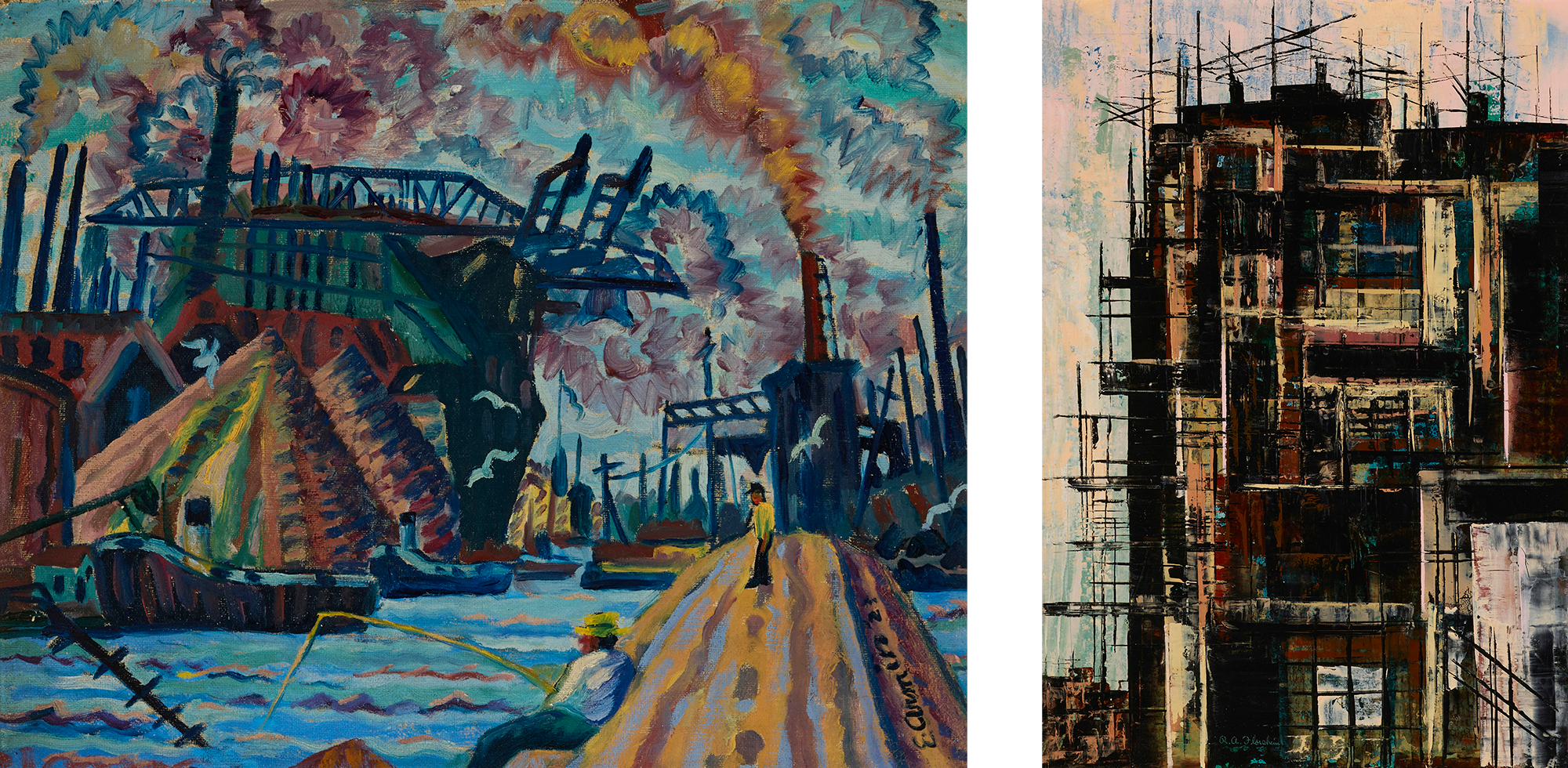

Broadly considered, Chicago Modernism includes works in a range of styles covering all manner of themes from the 1890s through the mid-20th century. From portraiture to landscapes, from still lifes to abstractions, and more, artists who were active in Chicago prior to the turn of the 20th century up through World War II helped to define the emerging city to itself and the world outside. This period featured notable artists producing finely executed and innovative examples of Impressionism, Realism, Abstraction, Regionalism, Surrealism, and Magical Realism. While connected to the major artistic currents in cultural centers like New York City and Paris, Chicago Modernism was able to develop in a relatively organic and original fashion given the Midwest’s geographic isolation and its tendency to be sometimes overlooked.

Following the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which certainly put the city on the map, in a literal and figurative sense, Impressionism, and its variants, began to take hold in Chicago, as it had already on the East Coast. When the modern era dawned, much of the Impressionist artwork done in Chicago contrasted rural and urban life or manifested as formal portraiture. Some of the key figures of this time were Oliver Dennett Grover, Adam Emory Albright, Frederick Fursman, Pauline Palmer, Frank C. Peyraud, Walter Krawiec, Carl Krafft, Karl Albert Buehr, and Alfred Juergens. The early decades of the 20th century also saw increased immigration to the United States, in particular, by Central and Eastern Europeans. In Chicago, some of these recent arrivals, and first-generation residents, sought to preserve their heritage while capturing the urban development around them. Among these were prominent Jewish-American artists like Emil Armin and Todros Geller, who exhibited with Grant Wood at the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as William Schwartz, Herman Menzel, Charles Turzak, and George Josimovich.

In the 1920s and 1930s, as the built environment of Chicago expanded, artists sought to represent this growth in their work. Many of these individuals were also employed by the New Deal-sponsored WPA (Works Progress Administration) Federal Art Project, which aimed to enhance the cultural fabric of America as the Great Depression threatened to fray the social contract. While there was some overlap aesthetically with work created by noted Regionalists like Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, the Chicago WPA artists operated in a variety of modes that ranged from Modernism to Art Deco to Abstraction. Around this time, the exceedingly versatile artist/designer Edgar Miller also began to make his mark on Chicago by blending elements of Arts & Crafts with Modernism in virtually every medium available.

Along with many of the European immigrants in Chicago, additional artists who were employed by the WPA to produce murals, paintings, prints, sculpture, and more included Jean Crawford Adams, Max Kahn, Eve Garrison, Roff Beman, Frances Foy, Harold Haydon, Rowena Fry, John Winters, Burton Freund, Hildreth Meiere, and countless others. The diversifying city was also represented in the WPA by artists of color like Eldzier Cortor, Archibald J. Motley, Jr., Jacob Lawrence, and Julio de Diego. Moreover, formally distinct Abstraction existed within Chicago Modernism by WPA artist Rudolph Weisenborn, as well as his student at the Art Institute of Chicago, Dorothy Stafford, along with the groundbreaking Manierre Dawson, Constructivist artist Paul Kelpe, Richard A. Florsheim, and Daniel Massen, who taught at the School of Design and the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Fantasy art afforded these [Chicago] artists a way of departing from tradition without abandoning many of its values: grounded in figuration and narrative, such art gave expression to highly personal visions in accordance with the aims of Modernism.” — Susan S. Weininger, Chicago Modern, 1893-1945: Pursuit of the New, Terra Museum of American Art, pg. 67

Modernism in Chicago further encompassed both Surrealism and Magical Realism. Given the city’s physical and cultural isolation, these fantasy-based art forms were able to flourish in unconventional, idiosyncratic ways. Gertrude Abercrombie, known as the “Queen of Bohemian Art,” was also a WPA artist, but, rather than presenting Chicago cityscapes or urban scenes, Abercrombie established herself on symbolic terrain. A master of self-portraits, Abercrombie inserted female figures into her beguiling works, but she was also fond of painting herself via owls, cats, horses, and other animals, or through elegantly simple still lifes with charged, everyday elements.

Among Abercrombie’s contemporaries were various highly skilled female artists, such as Julia Thecla, Helen Mann, and Margo Hoff, who each elaborated uniquely imaginative approaches to otherworldly effect. Macena Barton and Fritzi Brod were likewise accomplished fantasists whose work combined aspects of Expressionism and Folk Art. Milwaukee artist Karl Priebe trained at the Art Institute of Chicago and became known for his particular brand of Surrealism, with favorite subjects being portraits of Black figures he encountered teaching at a settlement house in Chicago as well as birds and exotic animals. Priebe was a longtime friend of Abercrombie's and they both were close with Wisconsin artist John Wilde—another proponent of Surrealism. Chicago native Aaron Bohrod faithfully chronicled local landscapes early in his career, before becoming adept at trompe-l’œil still lifes while an artist in residence at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. By contrast, Ivan Albright—son of Impressionist painter Adam Emory Albright—applied painstaking, classical techniques to render Modernism with a macabre vision and moody palette; his dark, high-relief portraits and still lifes provide a somber, yet undeniably compelling, counter to the soft brushstrokes and light-filled canvases of the Impressionists who ushered in Chicago Modernism over a half century before.

Not only did the many incarnations of Chicago Modernism serve to produce a robust aesthetic culture by the mid-20th century, but several of the aforementioned artists proved to be key influences for later generations. Gertrude Abercrombie, Eldzier Cortor, Todros Geller, and others have benefited from posthumous critical reevaluations, in which they have become more highly regarded now than they were during their lifetimes. Thematic and stylistic traces of Modernism may also be observed in the work of some artists associated with subsequent movements, such as the Monster Roster, Hairy Who?, and Chicago Imagists, proving that art history is indeed a continuum.

2: 12: 14

20|21 Art: Chicago Edition

11:00 am ct